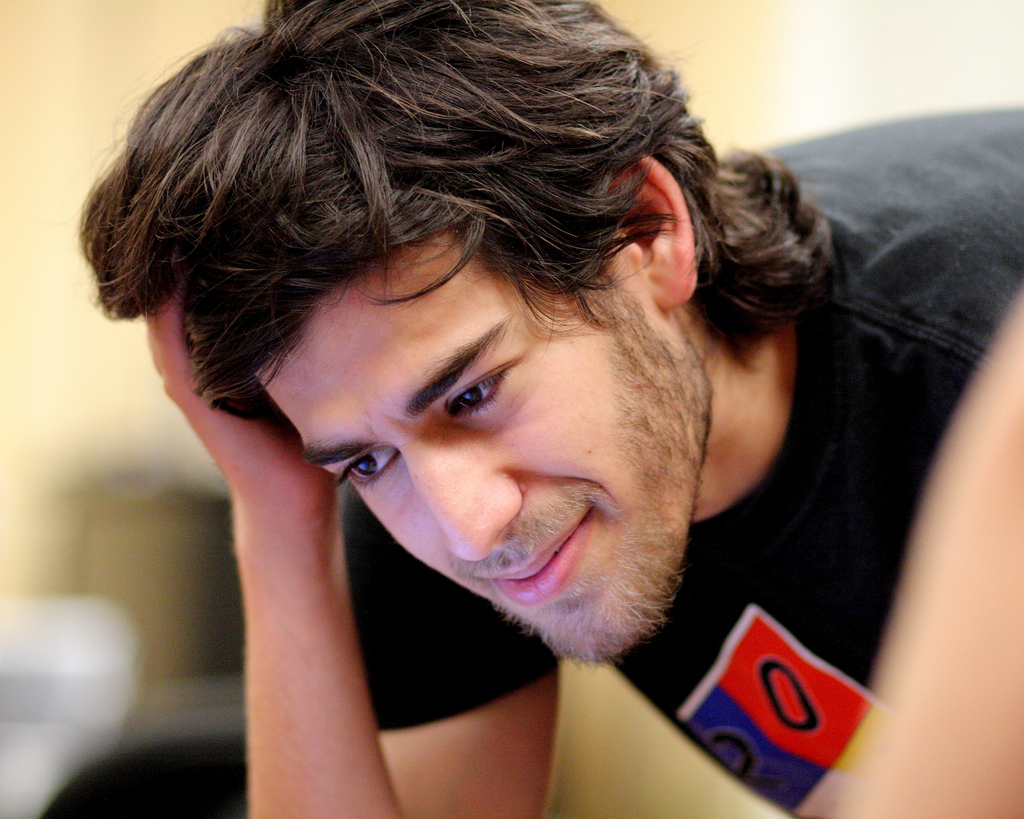

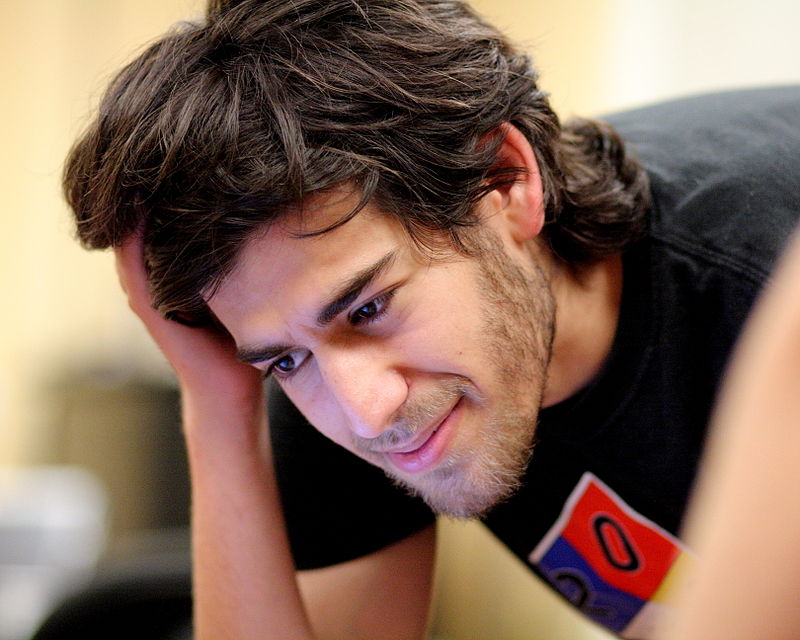

Last week was the beginning of something that might end up pretty huge in the world of free culture, copyright and open access activism. Aaron Swartz, a free knowledge activist hacker with ties to the Wikipedia community, was indicted by the federal government for allegedly downloading millions of files from JSTOR (an academic journal database) with the intent to distribute them on P2P networks. The actual charges aren’t for copyright infringement or anything directly related, however. They are for wire fraud, computer fraud and related offenses based on the way he allegedly obtained the files, by connecting to the MIT computer network and setting up scripts that downloaded files and dodged attempts to cut off access. (SJ Klein has a great overview of the charges and context.) Aaron never released this trove of files, and has reportedly turned them over to JSTOR.

He may have been planning to, however. You can get some insight into his thinking from the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto, which essentially advocates widespread and systematic sharing of restricted scholarship.

(The original is offline, but an apparently complete version that may or may not be authentic showed up on pastebin recently.)

In response to Swartz’s arrest, Wikimedian and free software developer Greg Maxwell actually did release a trove of JSTOR files: the complete archive of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (the longest-running scientific journal, started in 1665) through 1922. These have all entered the public domain in the legal sense, but not the practical sense. You can only get them under restrictive terms and/or for high prices (either through JSTOR or from the Royal Society).

You should read Greg’s whole essay. Here’s the conclusion:

If I can remove even one dollar of ill-gained income from a poisonous industry which acts to suppress scientific and historic understanding, then whatever personal cost I suffer will be justified — it will be one less dollar spent in the war against knowledge. One less dollar spent lobbying for laws that make downloading too many scientific papers a crime.

I had considered releasing this collection anonymously, but others pointed out that the obviously overzealous prosecutors of Aaron Swartz would probably accuse him of it and add it to their growing list of ridiculous charges. This didn’t sit well with my conscience, and I generally believe that anything worth doing is worth attaching your name to.

A lot of free culture and open access advocates draw a line between Aaron and Greg. Greg is praised for taking his stand, but few are endorsing Aaron’s alleged actions, only condemning the gross disparity between the charges and the alleged actions — while ignoring or opposing the argument of the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto. (That line between them is copyright law.)

Me, I’m not so sure. I’m not sure copyright law has enough moral force to be a meaningful distinction. I’m certainly not convinced terms of use have enough moral force to matter here. The bottom line is, the world of academic publishing and distribution is changing… but painfully slowly. Academic publishing isn’t cheap, professional-grade digitization of old journals isn’t cheap, and there’s no single fix for keeping everything people like about academic publishing and archiving (like peer review and professional editing and easily searchable databases) while getting rid of what we don’t like (like paywalls), without totally upending the industry. Greg-ites — who liberate public domain material — and Aaron-ites — who want to liberate all scholarship, copyright be damned — both have the same practical consequences: to push paywalls and organizations that rely on them closer to irrelevance, and to place the burden of organizing and indexing and providing access onto open knowledge communities and organizations (and big data companies like Google).

I lean toward thinking that’s a good thing.