In my first post to Revise and Dissent, I lamented that historians don’t have good answers to the question: “Why does your work matter to anyone who is not an historian?” I heard two very engaging talks over the last 8 days, from two historians of science and medicine with very different takes on the issue.

Last week, Alice Dreger gave probably the most provocative colloquium talk I’ve heard at Yale. Dreger is an intersex rights activist and “medical humanist” who has worked to change the barbaric practices of genital surgery for children with disorders of sex development (or whatever you want to call the conditions; terminology is a charged issue here), often without even informing the parents. She also became involved in recent controversies over transsexualism and the book The Man Who Would Be Queen, and she’s written social/medical histories of hermaphrodites and “unusual anatomies”.

In a great talk that simultaneously made her seem brazenly self-promoting and bracingly altruistic, Dreger explained how she has been doing what she calls “onion-peeling”: private histories about individuals (shared only with the subject) that place people’s lives, or specific traumatic events in their lives, into historical context. She described how powerful these short (4-6 pages, usually) self-contained histories were to their subjects. For many, reading their own history in someone else’s words was a cathartic experience that let them understand and accept their pasts (e.g., why a doctor had performed an infant clitoridectomy, and why their family had never discussed the issue during childhood).

These personal histories are nearly useless for doing academic history, since they are performed on the explicit condition of privacy and the subject-driven interview-and-revision procedure introduces grave reliability problems by normal oral history standards. As Dreger explained it, the main benefit of doing these “onion-peelings” is the personal satisfaction of seeing your work have a direct and substantial positive impact on someone’s life. She hinted that she sees normal history as a powerful force for social good as well, but with effects that are harder to see (and so harder to feel good about). The end-game of the talk was that Dreger is considering starting a non-profit to help other historians do “onion-peeling” (client-centered histories), and maybe even provide funding for them to do so.

Topics of discussion after the presentation included: the line between onion-peel history and psychoanalysis; legal and emotional liability; the permissibility of glossing over historical ambiguity for the benefit of an audience of one; and how such pro bono work could fit into the expectations of modern academia. I, for one, find the idea of client-centered histories compelling, but not something I would actually consider doing. It’s a better answer to the blog title question than nothing, but I think there are more efficient (though maybe not as personally rewarding) ways for historians to serve the public, if they are actually willing to do something outside the professional norms.

Today, William Newman gave a talk on why Newton (and many other smart people in the 17th and 18th centuries) practiced alchemy, and how there was a smooth transition from alchemy to chymistry to chemistry. Even Lavoisier, says Newman, was doing basically the same kinds of things Newton had been doing a century before–just with more sophisticated and precise apparatus (and a clever theory of combustion). Despite substantial treatments of Newton’s alchemy by earlier historians such as Richard Westfall, Newman thinks that most work on the Scientific Revolution is badly flawed because early historians of alchemy didn’t understand the technical aspects of alchemy (and so overemphasized the metaphorical and occult aspects).

Newman and others have been working out what Newton was actually doing in his workshop. (He described a Newton not so different from the character in The Baroque Cycle.) Newman did a live alchemy demonstration, showing how certain minerals would show signs of life (substances that form fast-growing crystals when put in a chemical solution, e.g., a “silica garden“), and how nitric acid could be (and was) used supposedly to transmute silver into gold (by depletion gilding). Newman explained why transmutation was part of the agenda of the legitimate, “scientific” alchemists like Newton: in the 17th century there was no NSF; the promise of transmutation was a sort of “grant application” of sorts, which he compared to modern justifications for research funding that promise a cure for cancer (which the young field of molecular biology used to great effect in the 1950s and ever since, but with a cure still seeming as far off as ever.) Transmutation wasn’t inconceivable, but the alchemists had more practical, immediate goals for their work and would use the lure of unlimited alchemical wealth for their patrons to their own ends.

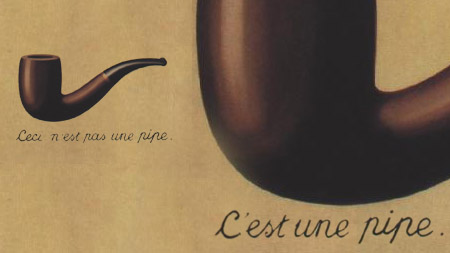

With NSF funding, Newman is building a complete online collection of Newton’s alchemy manuscripts (which are scattered about the globe, since many were auctioned off in the early 20th century): The Chymistry of Isaac Newton. The site has seen considerable popular interest; there is a lot of enthusiasm about Newton among non-historians. But when I asked Newman “Why does your work matter to anyone who is not an historian?”, he stumbled. (This after his eloquent, obviously well-practiced explanation of why it matters to other historians of science). Answering that question, he said, is like “tilting at windmills”; historical myths like Columbus discovering that the Earth is round persist, even though historians have known them to be false for several generations. The misinformed “army of middle-school teachers” create a closed loop of misinformation that propagates from generation to generation, a seemingly insoluble problem.

Myths about alchemy (and the flat earth, and the conflict between science and religion, and Ptolemaic astronomy, and many others) are doubly pernicious and recalcitrant because they serve as a purpose, as foil for their modern counterparts. Newman is pessimistic that any significant changes in public (mis)perceptions of the history of science are possible, since these myths acquire their own momentum.

I think Wikipedia is changing that, and changing the whole way the public uses and understands history–e.g., see Flat Earth and Flat Earth mythology–but that’s a topic for another post (and for the article for the History of Science Society Newsletter that I’m working on). If you got this far, thanks, and sorry for the blogorrhoea.

[Cross-posted at Revise and Dissent]

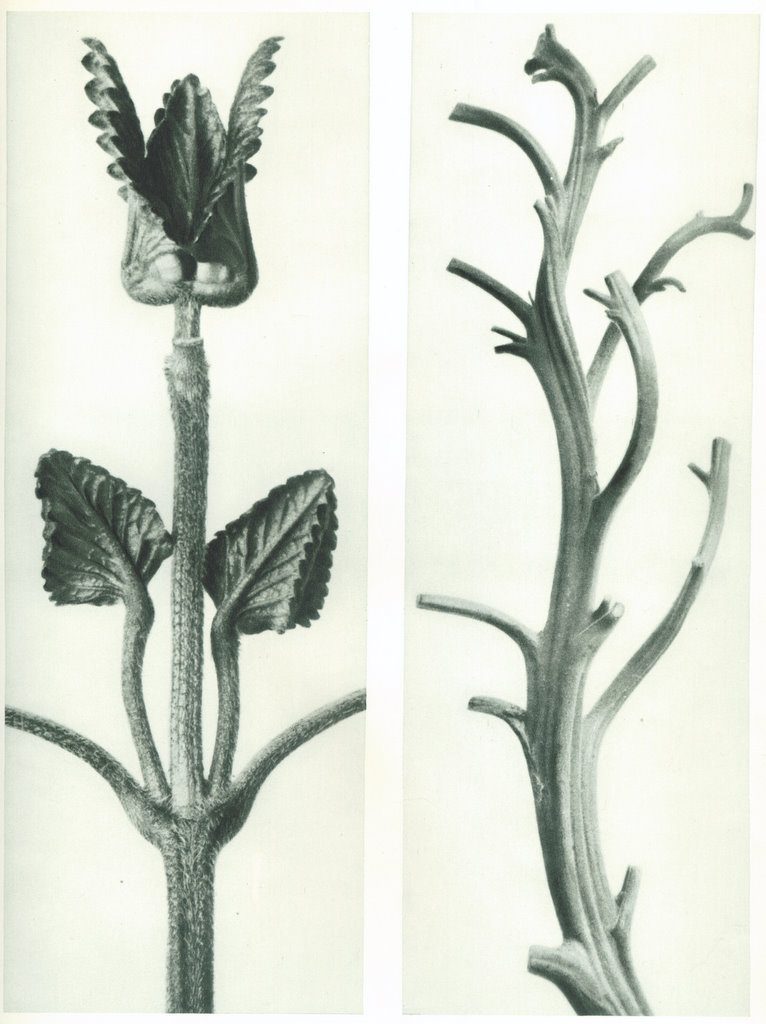

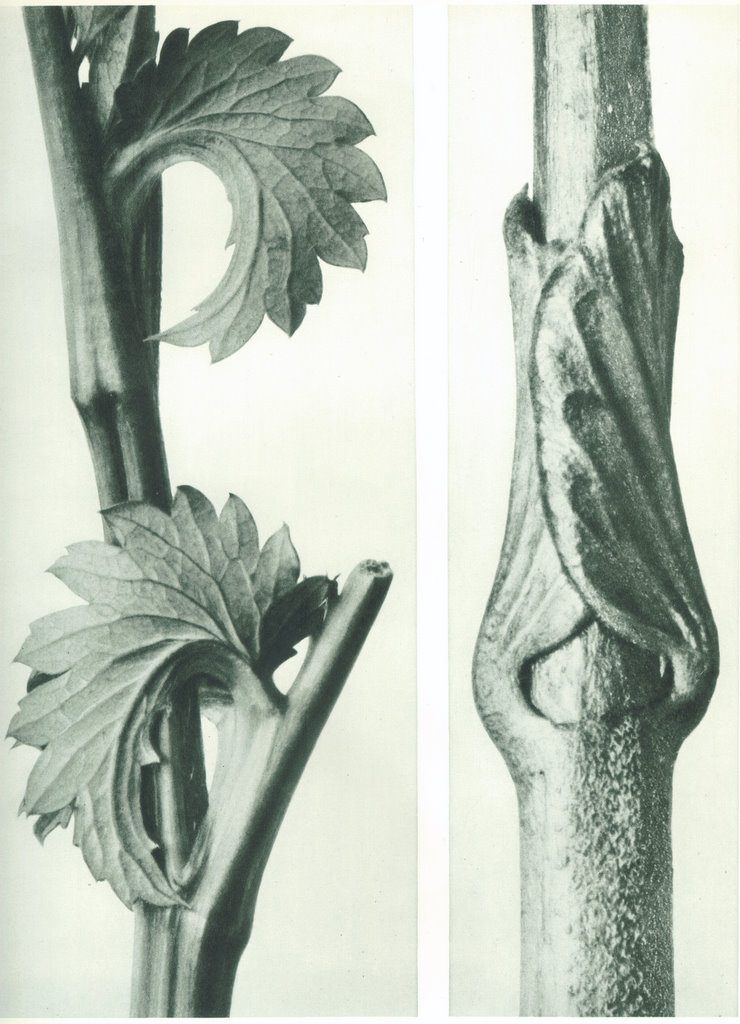

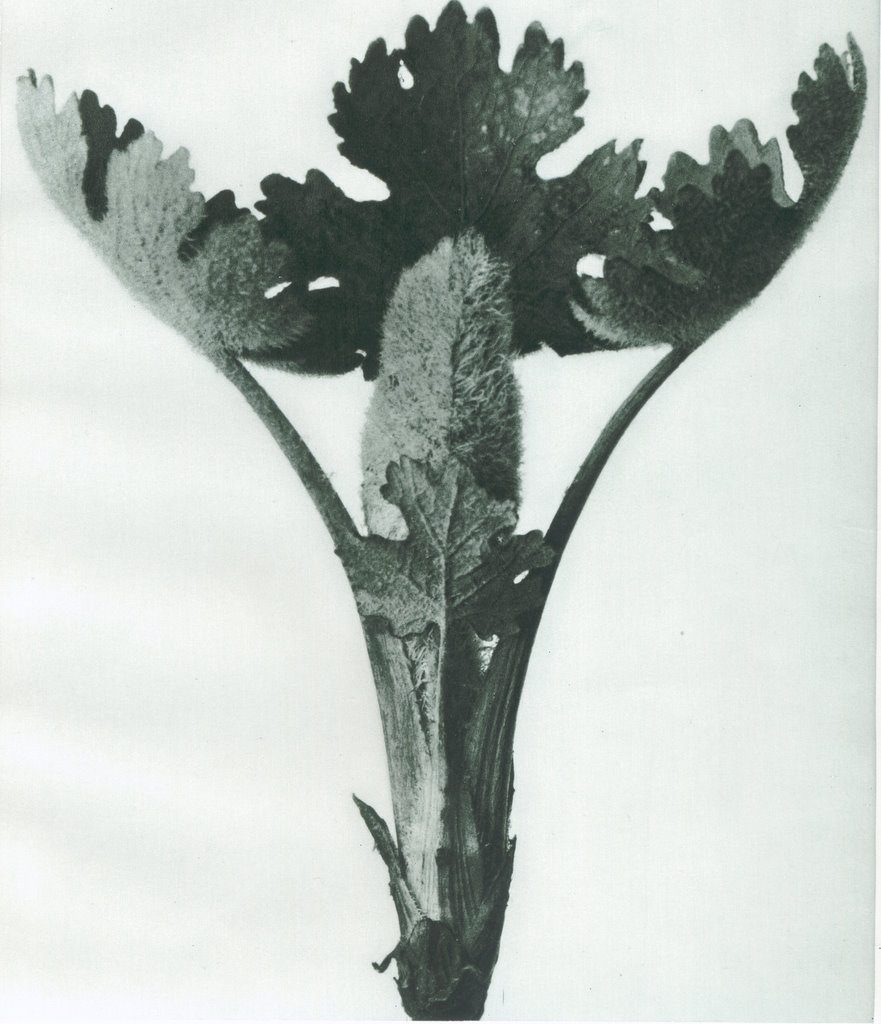

And finally, I won an eBay auction on a trio of 1929

And finally, I won an eBay auction on a trio of 1929