Joseph Reagle‘s Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia is a major step forward for understanding “the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit” and the community that has been building it for the past decade. Based on Reagle’s dissertation, the book takes a broadly humanistic approach to exploring what makes the Wikipedia community tick, combining elements of anthropology, sociology, history, and science & technology studies.

The book opens with an example of how Wikipedia works that turns the famous “Godwin’s law” on its head: unlike the typical Internet discussion where heated argument gives way to accusations of Nazism, Wikipedians are shown rationally and respectfully discussing actual neo-Nazis who have taken an unhealthy interest in Wikipedia. This theme of “laws” carries throughout the book, which treats the official and unofficial norms of Wikipedia while turning repeatedly to the humorous and often ironic “laws of Wikipedia” that contributors have compiled as they tried to come to an understanding of their own community.

Reagle’s first task is to put Wikipedia into historical context. It is only the most recent in a long line of attempts to create a universal encyclopedia. And what Reagle shows, much better than prior, more elementary pre-histories of Wikipedia, is just how much Wikipedia has in common–in terms of aspiration and ideology–with earlier efforts. The “encyclopedic impulse” has run strong in eccentrics dating back centuries. But the real forerunners of Wikipedia come from the late 19th and early 20th centuries: Paul Otlet’s “Universal Bibliographic Repertory” and H.G. Wells’ “World Brain”. Both projects aspired to revolutionize how knowledge was organized and transmitted, with implications far beyond mere education. Just as the Wikimedia Foundation’s mission statement implies–“Imagine a world in which every single human being can freely share in the sum of all knowledge…”–Otlet and Wells saw Utopian potential in their projects. Those efforts were based on new technologies–index cards and microfilm–and each new wave of information technology since then has inspired another attempt at a universal knowledge resource: Project Xanadu, Project Gutenburg, Interpedia, Distributed Encyclopedia, Nupedia, GNUpedia. Wikipedia, Reagle argues, is the inheritor of that tradition.

Next, Reagle sets out to capture the social norms that the Wikipedia community uses as the basis for its communication and collaboration practices. These will be very familiar to Wikipedians, but Reagle does a nice job of explaining the concepts of “neutral point of view” and the call to “assume good faith” when working with other editors, and how these two norms (and related ones) underlay Wikipedia’s collaborative culture. Of course, Reagle readily recognizes that these norms have limits, and one doesn’t have to go far into Wikipedia’s discussion pages to find examples where they break down. But understanding the aspirations of the community in terms of these norms is the first step to an overall picture of how and why Wikipedia works (and, at times, doesn’t work).

Reagle then turns to consider the “openness” of Wikipedia, which is an example of what he calls an “open content community”. Wikipedia’s effort to be the “encyclopedia that anyone can edit” means that inclusiveness creates a continual set of tensions–between productive and unproductive contributors, between autonomy and bureaucracy, between transparency and tendency of minorities to form protected enclaves.

Decisionmaking and leadership on Wikipedia are even bigger challenges than openness. In successive chapters, Reagle examines the concept of “consensus” as practiced by the Wikipedia community and the role that founders Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger played in setting the early course of the project.

The ideal of consensus was inherited from earlier open technical communities like the Internet Engineering Task Force, whose credo declares “We reject: kings, presidents and voting. We believe in: rough consensus and running code.” But that ideal doesn’t map precisely onto Wikipedia, in part because the “running code” of Wikipedia content isn’t as easy to evaluate as a computer program. Reagle also draws in intriguing comparison between Wikipedia’s still-unsettled notions of consensus and the practices of a more mature consensus-based community: the Quakers. Wikipedia lacks some of the roles and traditions that support decision-making in Quaker groups, and one implication of Reagle’s discussion is that Wikipedians might be able to learn a lot about effective consensus-based governance from the Quakers.

The lasting imprint of Wikipedia’s founders, the “good cop” Wales and the “bad cop” Sanger, has been treated a number of times before. But Reagle’s is the clearest account yet of how the tension between their different ideas for how to structure a voluntary encyclopedia project played out. Especially in the early years of Wikipedia, Wales’ role was primarily focused on maintaining a healthy community and balancing the perspectives of community members, highlighting good ideas and attempting to build consensus rather than promoting his own specific ideas. Even from early on, though, Wales’ role as “benevolent dictator” (or “God-King”, in the negative formulation) was a source of tension. Reagle notes that this tension is a recurring feature in open content communities; even the half-joking titles given to Wales are part of a broader tradition that traces to early online communities.

From my perspective as a Wikipedian–already familiar with norms and much of the short history of Wikipedia–the most powerful part of the book is the discussion of “encyclopedic anxiety”. Reagle argues that reference works have long provoked reactions from broader society that say more about general social unease than the specific virtues and faults of the reference work at hand. Wikipedia is a synecdoche for the changes taking place in information technology and the media landscape, and has served as a reference point for a wide gamut of social critics exploring the faults and virtues of 21st century online culture. That is not to say criticism of Wikipedia is always, or even usually, off-base. But what critics latch onto, and what they don’t, involves the interplay of the reality of Wikipedia and its role as a simultaneous exemplar for many social currents and trends.

Good Faith Collaboration is an enjoyable read, erudite but well-written and straightforward. It will be required reading for anyone serious about understanding Wikipedia.

*disclaimer: I consider Joseph Reagle a friend, and he thanks me in the preface. I read and commented on early versions of parts of the book. At the time of writing this review (October 2010) I also work for the Wikimedia Foundation, the non-profit that runs Wikipedia. But neither of those factors would stop me from being harsh if I thought the book deserved it. The review represents my personal opinion.

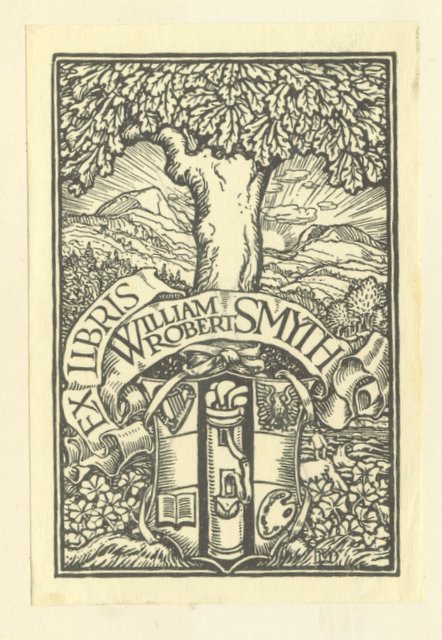

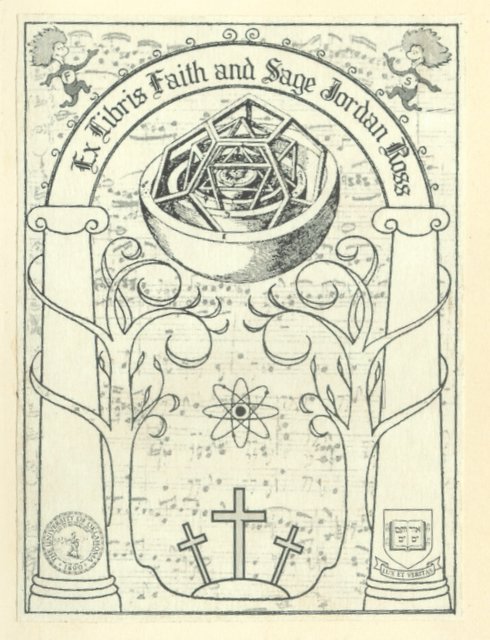

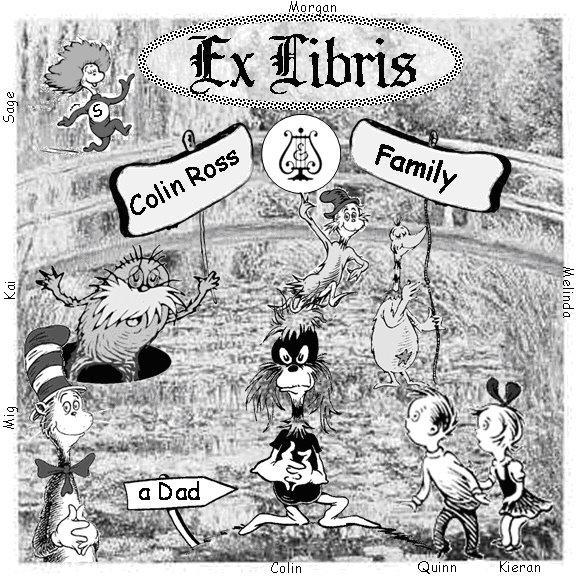

I had never heard of “ex libris” before, but that’s what really made the book-buying experience for me, and inspired me to make my own. Since then, the miracles of eBay and alibris.com have brought me plenty of material to stock my shelves, and a few more bookplates.

I had never heard of “ex libris” before, but that’s what really made the book-buying experience for me, and inspired me to make my own. Since then, the miracles of eBay and alibris.com have brought me plenty of material to stock my shelves, and a few more bookplates.

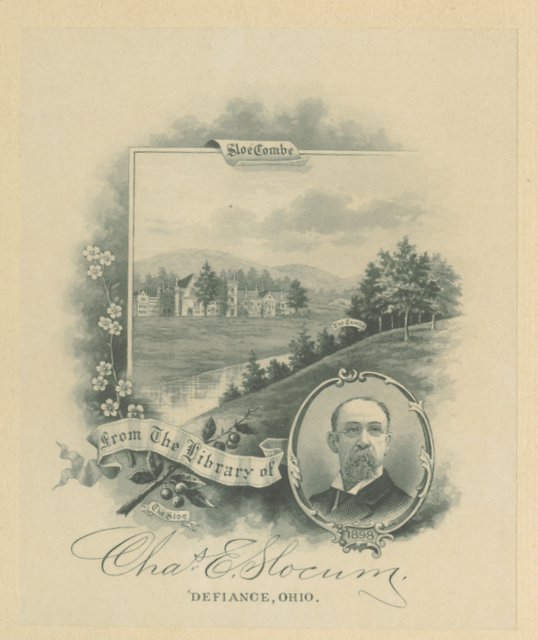

Another interesting bookplate came in each of two volumes of

Another interesting bookplate came in each of two volumes of  Cha[rle]s E[lihu] Slocum wrote a book in 1909 on the dangers of tobacco, and he has an elementary school and I think a few other things named after him.

Cha[rle]s E[lihu] Slocum wrote a book in 1909 on the dangers of tobacco, and he has an elementary school and I think a few other things named after him.