A few weeks ago, thanks to the blog A Journey Round My Skull (via Crooked Timber), I discovered Biology Today, an amazing college biology textbook from 1972. You can get the basics from the Wikipedia article I put together: [[Biology Today]]. But there’s a lot more to it than what I could put into a Wikipedia article without running afoul of the “no original research” policy–and a lot more than I can fit into a blog post. The reviewer of a bowdlerized later edition got it right: “The true story of the development of Biology Today would make an interesting book in itself.”

The text of Biology Today was apparently assembled from the work of a long list of “contributing consultants”. The list is star-studded, including James D. Watson and six other Nobel laureates (as well as Michael Crichton). The list–and the text–is dominated by molecular biology, which was reaching perhaps its cultural acme in the early 1970s.

A Journey Round My Skull has collected on Flickr many (but far from all) of the interesting and unusual “artist’s interpretations” and other images that make Biology Today such a magnificent artifact. Many of the diagrams are outstanding both aesthetically and conceptually.

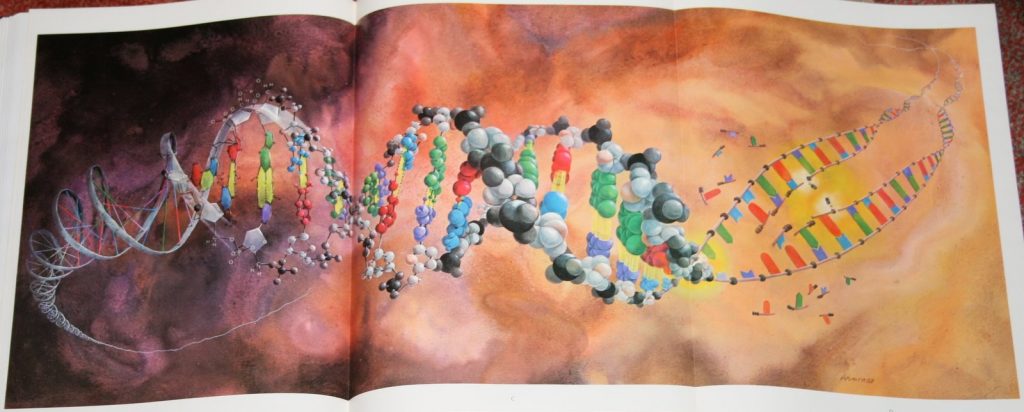

The most lavish interleaf illustration is supposed to depict the “central dogma” of molecular biology with a three-panel view into the holy of holies, the DNA-filled nucleus, and a two-panel view of nucleic acids making their way into the cytoplasm and translating genetic information into proteins:

Molecular biologists, by the 1970s, thought of themselves not only as the future of science, but of culture more generally. Many adopted the scientific humanism that had been championed by the previous generation of public biologists like Julian Huxley, although the mechanistic and cybernetic worldview of molecular biology, rather than the neo-Darwinism of Huxley and his allies, was their gospel. For intellectually- and sexually liberated biologists (like Watson), anthropology and sexology displaced parochial religious ideas, and science had nothing to offer religionists but contempt or pity. Behold Noah’s Ark, from the chapter on “Human Sexual Behavior”:

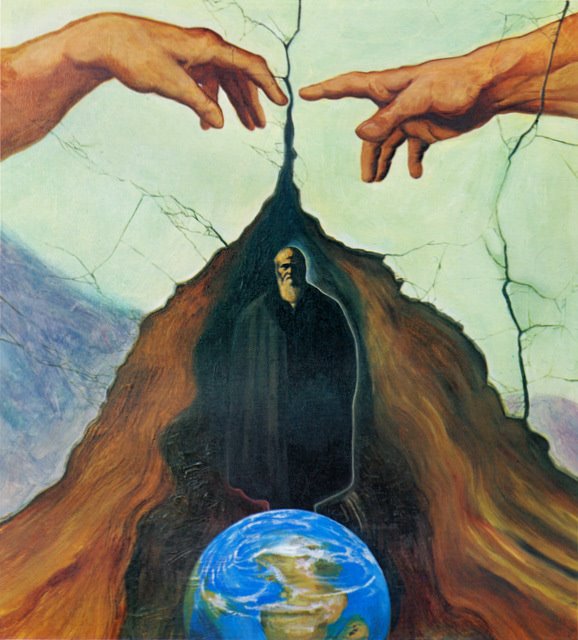

Evolution’s role in this textook is a curious one. The only well-known figure who can be considered primarily an evolutionary biologist is Richard Lewontin, a pioneer of molecular evolution and a frequent critic of adaptationism, sociobiology, and much of mainstream evolutionary theory in the 1960s and 1970s. The chapter on population genetics, which introduces the mechanisms of evolution (and doesn’t come until page 672!) looks like it was written by Lewontin; it treats, in turn, “genetic equilibrium”, “genetic drift”, “mutation”, “selection”, and “multiple factors”, with no particular emphasis on natural selection. Of course, whether one was a follower of the selection-centric modern evolutionary synthesis or not, Darwin was (and still is) the patron saint of biology:

But in Biology Today, veneration of nature, of the scientific life, and of humanity trumped veneration of Darwin. In the lyrical ten-page illustrated preface from biochemist Albert Szent-Györgyi, there is a passage (one of many) that could never be found in a mainstream biology textbook today, when creationists have turned their energies (in the form of Intelligent Design) to molecular biology, rather than the organismal evolutionary biology that earlier generations of creationists (and evolutionists) focused on. Working his way up through the levels of biological complexity, Szent-Györgyi makes his way to the mind:

“I do not think that the extremely complex speech center of the human brain, involving a network formed by thousands of nerve cells and fibers, was created by random mutations that happened to improve the chances of survival of individuals. I must believe that man built a speech center when he had something to say, and he developed the structure of this center to higher complexity as he had more to say. I cannot accept the notion that this capacity arose through random alterations, relying on the survival of the fittest. I believe that some principle must have guided the development toward the kind of speech center that was needed.”

For both cultural and scientific reasons, that’s not something you would catch many biologists saying today.