Maybe I’m weird, but I’m really excited about the prospect of high profile copyright/fair use litigation. As the New York Times reports, the Associated Press sued street artist Shepard Fairey over the Obama “Hope” poster, which was based on a shot by former A.P. freelance photographer Mannie Garcia.

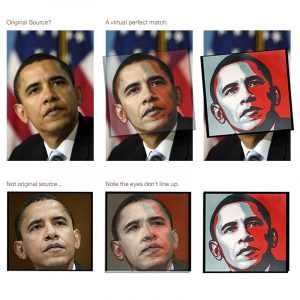

A few weeks ago, I started the Wikipedia article on the poster. It ended up on the Main Page for “Did you know?” on inauguration day, and while it was there another editor, Dforest, pointed me to something very interesting: this Flickr photo by stevesimula (shown above). When I wrote the article, it was thought (and reported) that the lower shot (a Reuters photo by Jim Young) was the basis for Fairey’s poster. But stevesimula had convincingly demonstrated the true source, which apparently was known only to Fairey (and probably some of his crew), some of the Obama people, and whatever isolated netizens might have noticed. (I investigated some rumors that an art forum had found it months earlier, but couldn’t verify that.)

This was getting interesting, but beyond what was allowed on Wikipedia without violating the ban on Original Research. Long story short, I started a Wikinews article on the photo source, and a tip from Dforest and me (that the photo was from A.P., which we found with TinEye.com) led photographer Tom Gralish to find a copy of the original that included metadata, identifying the photographer. If we’d just been a little smarter, we might have beaten Gralish to the punch and broken a story of national import.

Now A.P. has sued Fairey (who didn’t profit directly from Obama poster sales, but no doubt has seen a huge surge in interest in his other for-profit work) for violating its copyright. Fairey, assisted by a Stanford law proffesor among others, is suing back, seeking a declaratory judgment that the poster is fair use. To make it even better, Mannie Garcia claims he actually owns the copyright, because of the terms of his A.P. contract.

I’m a big supporter of fair use, but this is an interesting case of pushing the boundaries. The main reason I’m ambivalent is the way Fairey handled it… he originally appropriated the image with no attempt at crediting Garcia. Fairey has obviously benefitted tremendously (if not directly, in terms of profit) from the image, but has also dramatically increased the value of the original. His work is also essentially a political statement, something fair use is supposed to protect and allow. But the hybrid nature of Fairey’s commercial street art (controversial even within the street art scene) complicates things. Either you’re doing this essentially anti-authoritarian street art that is based on grafitti culture, or you’re running an art business. If it’s the former, go ahead and break the rules you disagree with or don’t care about, but don’t expect to be making the big bucks mass-producing and selling your designs. If it’s the latter, you should at least have the decency to credit other artists whose work you use for your own.

I’m really rooting for Garcia, here. From all the snippets I’ve read, he seems gracious and thoughtful. From the Times:

“I don’t condone people taking things, just because they can, off the Internet,” Mr. Garcia said. “But in this case I think it’s a very unique situation.”

He added, “If you put all the legal stuff away, I’m so proud of the photograph and that Fairey did what he did artistically with it, and the effect it’s had.”

But I’m also rooting for Fairey, or at least for the entrenchment of liberal fair use rights.

For the last week, I’ve been exchanging emails with curators at the

For the last week, I’ve been exchanging emails with curators at the  Taking pictures to illustrate Wikipedia articles is the reason I got into photography. I started with my wife’s point-and-shoot, and pretty soon I started to appreciate the joys of photography for their own sake…and I started to experience that strong desire for better and still better equipment. A few weeks ago I finally realized my long-time goal of shooting an original Featured Picture (FP), this ‘Peach Glow’ water lily.

Taking pictures to illustrate Wikipedia articles is the reason I got into photography. I started with my wife’s point-and-shoot, and pretty soon I started to appreciate the joys of photography for their own sake…and I started to experience that strong desire for better and still better equipment. A few weeks ago I finally realized my long-time goal of shooting an original Featured Picture (FP), this ‘Peach Glow’ water lily.