After Aaron Swartz committed died by suicide in January, and in the months since then as issues of internet freedom and his own tragic story have continued to make news, there’s been a lot of demand for photos of Aaron. I had three photos of him up on Flickr and Wikimedia Commons, from a 2009 Wikipedia meetup.

(I went back to my archives and found several more from that meetup.)

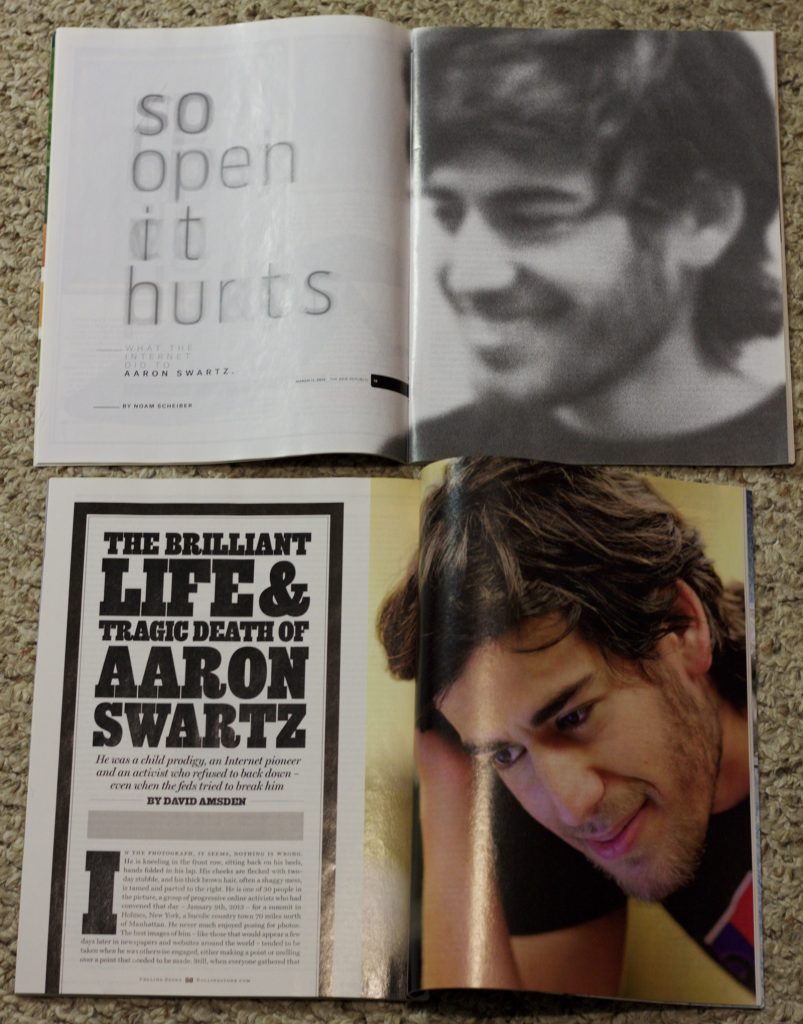

When I got contacted by photo editors who wanted to use these photos, I tried to get them to follow the terms of the CC-BY-SA license. In two cases, Rolling Stone and New Republic, I got a chance to explain how to use a Creative Commons license in print. For most photo editors, free licenses are a big unknown, but lately (in my anecdotal experience) they’ve been more willing to use and follow the licenses than in years past. Here are the spreads.

I’ve tried to follow how these photos have been used online, as well, to understand how–and how well–freely licensed images are used by news websites. Of the 42 uses I’ve looked at there are:

- 6 that follow the license, or come close enough. (If they include a link to the original on Commons or Flickr, I count it as close enough, since others will be able to find all the attribution and license info, even if the reuser isn’t following the license to the letter.)

- 9 that provide attribution to me, but do not follow the license (ie, there’s no indication that the file is freely licensed). Among these is the long Slate profile that is also sold as a Kindle ebook… but with no attribution in the ebook that I can tell.

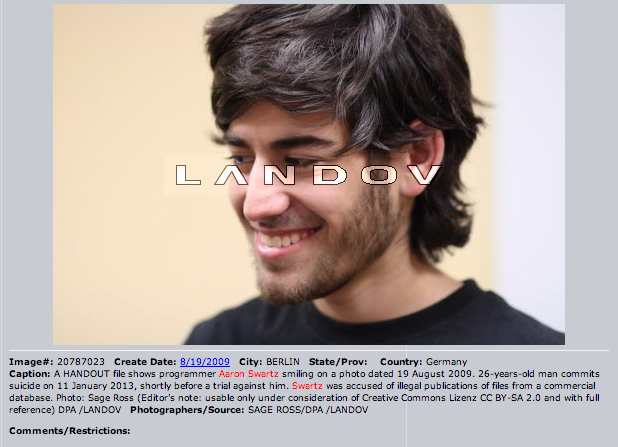

- 9 (most of which credit me) that add an illegitimate attribution to photo agencies: DPA/Corbis, DPA/Landov and such. Among them: Business Week, New York Magazine, New Scientist, and Bloomberg.com. Two from time.com did not initially credit me, only the photo agencies, but the credits were updated after @wikisignpost contacted them. A few others still don’t. I’m not sure how the photo got appropriated into (I assume) DPA’s collection, but they seem to be distributing it widely and internationally.

- 18 that provide no attribution. In addition to the Amazon ebook version of the Slate piece, the more significant places that don’t use any attribution include the Boston NPR station, Democracy Now, and a Fast Company piece by the project lead of Creative Commons Brazil.

Probably the most interesting use is this mixed media derivative (unattributed, and with no free licensing that I can tell) from a Hungarian website. If anyone knows the language and wants to try to get them to release it under a free license, please do.

UPDATE

The time.com writer put me in touch with their photo editor, who sent me a screenshot from the Landov website, showing how my photo appears in the photo licensing database. The last part of the Caption section reads:

The last part of the Caption section reads:

Photo: Sage Ross (Editor’s note: usable only under consideration of Creative Commons Lizenz CC-BY-SA 2.0 and will full reference) DPA/LANDOV

But the Comments/Restrictions section is blank, and the Photographers/Source line that news orgs would typically use just says SAGE ROSS/DPA/LANDOV. So basically they are charging news organizations for this photo and hiding away the fact that it’s not their photo to license in the normal way, and that if their customers want to use it, they actually have to follow the same rules as everyone who gets it for free from the original source.