Digital opinion-makers across the blogosphere and the twitterscape been increasingly preoccupied with the rapid decline of the print news industry. Revenues from print circulation and print advertising have both shrunk dramatically, and internet advertising revenues have so far been able to replace only a fraction of that. Newspapers throughout the U.S. are downsizing, some are switching to online-only, and some are simply being shuttered. The question is, what, if anything, will pick up the journalistic slack. (Clay Shirky’s essay, “Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable“, is the best thing I’ve seen in this vein, although I would be remiss if I didn’t mention some contrasting viewpoints, such as Dave Winer’s “If you don’t like the news…” and Jason Pontin’s response to Shirky and Winer, “How to Save Media“.)

On its face, Wikinews seems an ideal project to pick up some of that slack. Collaborative software + citizen journalism + brand and community links to Wikipedia…it seems like a formula for success, and yet Wikinews remains a minor project. There are typically only 10 -20 stories per day, most of which are simply summaries of newspaper journalism. Stories with first-hand reporting are published about once every other day, and even many of these rely primarily on the work of professional journalists and have only minor original elements.

Why doesn’t Wikinews have a large, active community? What might a successful Wikinews look like? I have a few ideas.

One reason I write and report for Wikipedia regularly, but only every once in a while for Wikinews, is that writing Wikipedia articles (and writing for the Wikipedia Signpost) feels like being part of something bigger. Everything connects to work that others are doing. I know I’m part of a community working for common goals (more or less). Even if I’m the only contributor to an article, I know there are incoming links to it, that it fits into a broader network. On Wikinews, I can write a story, but it is likely to be one of maybe 20 stories for the day, none of which have much of anything to do with each other.

I went to the Tax Day Tea Party in Hartford, Connecticut with my camera and a notepad. (I put a set of 108 photos on Commons and on Flickr.) Similar protests reportedly took place in about 750 other cities. If there was ever an opportunity for collaborative citizen journalism, this seemed like it. But there was nothing happening on Wikinews, and I didn’t see the point writing a story about one out of hundreds of protests, which wouldn’t even be a legitimate target for a Wikinews callout in the related Wikipedia article.

What I take from this is the importance of organization. Wikinews needs a system for identifying events worth covering before (or while) they happen and recruiting users for specific tasks (e.g., “find out the official police estimate of attendance, photograph and/or record the messages of as many protest signs as possible, and gather some quotes from attendees about why they are protesting”).

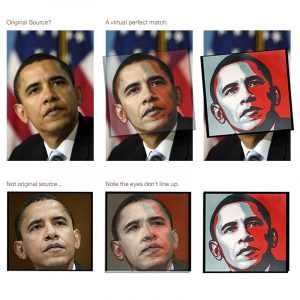

My most rewarding experience with Wikinews was a story on the photographic origins of the Obama HOPE poster. It grew out of a comment on the talk page of the poster’s Wikipedia article; the comment appeared while it was on the Main Page as a “Did you know” hook. The lesson here is, in the (alleged) words of Clay Shirky, “go where people are convening online, rather than starting a new place to conveve”. (I think it was unfortunate that Wikinews started as a separate project rather than a “News:” namespace on Wikipedia, but what’s done is done.) There are many places online people gather to discuss and produce news, in addition to Wikipedia; one path to success might be to extend the social boundaries to Wikinews to reach out to existing communities. Although other citizen journalism and special interest communities don’t share the institutional agenda of Wikinews (name, NPOV as a core principle), some members of other communities will be willing to create or adapt their work to be compatible with Wikinews’ requirements. And certain communities actually do share a commitment to neutrality, which raises the possibility of syndication arrangements (in which, e.g., original news reports from a library news automatically get added to the Wikinews database as well).

Shirky and others have argued that some kinds of journalism (in particular, investigative journalism) are not possible without assigning or permitting reporters to develop a story in depth over a long period of time–and these may be the most important kinds of journalism for maintaining a healthy democracy. To some extent, alternative finance models (with public donations like National Public Radio or with endowments like The Huffington Post ) may be filling some of the void left by shrinking newpaper staffs, but it seems unlikely that these models will support anything close to the number of journalists that newspapers do/did.

Wikinews could contribute to investigative journalism in a couple of ways. The simplest is something similar to what Talking Points Memo does–crowdsourcing the analysis of voluminous public documents to identify interesting potential stories. However, as Aaron Swartz recently argued, there are serious limits to what can be gleaned from public documents; as he says, “Transparency is Bunk“.

Another way would be to either fund a core of professionals or collaborate with investigative journalists who work for other non-profits. These professional journalists would–to the extent that it is possible–recruit and manage volunteer Wikinewsies to pursue big stories where the investigative work required is modular enough that part-time amateurs can fruitfully contribute.

In the same vein a professional editor working for Wikinews could be in charge of identifying self-contained reporting opportunities based on geography (e.g., significant political and cultural events) and running an alert system (maybe integrated with the Wikipedia Geonotice system for users who opt in) to let users know what’s happening near them that they could report on. One of the hardest things for a would-be Wikinewsie original reporter is just figuring out what needs covering.

I’m sure there there are a lot of different models for Wikinews that could make it into a successful project. But it’s clear that the current one isn’t working very well.