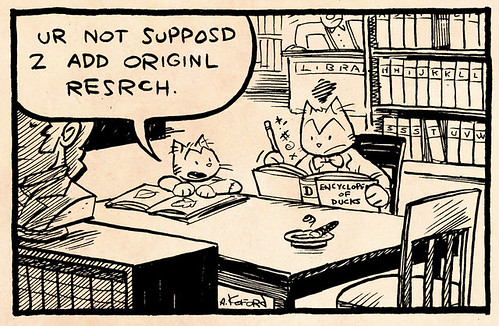

The zeroeth law of Wikipedia states: “The problem with Wikipedia is that it only works in practice. In theory, it can never work.”

That’s largely true of the kinds of theory that are most closely related to the hacker-centric early Wikipedia community: analytical philosophy, epistemology, and other offshoots of positive philosophy–the kinds of theory most closely related to the cultures of math and science. (See my earlier post on “Wikipedia in theory“.) But there’s another body of theory in which Wikipedia’s success can make a lot of sense: Marxism and its successors (“critical theory”, or simply “Theory”).

A fantastic post on Greg Allen’s Daddy Types blog, “The Triumph of the Crayolatariat“, reminded me (indirectly) of how powerful Marxist concepts can be for understanding Wikipedia and the free software and free culture movements more broadly.

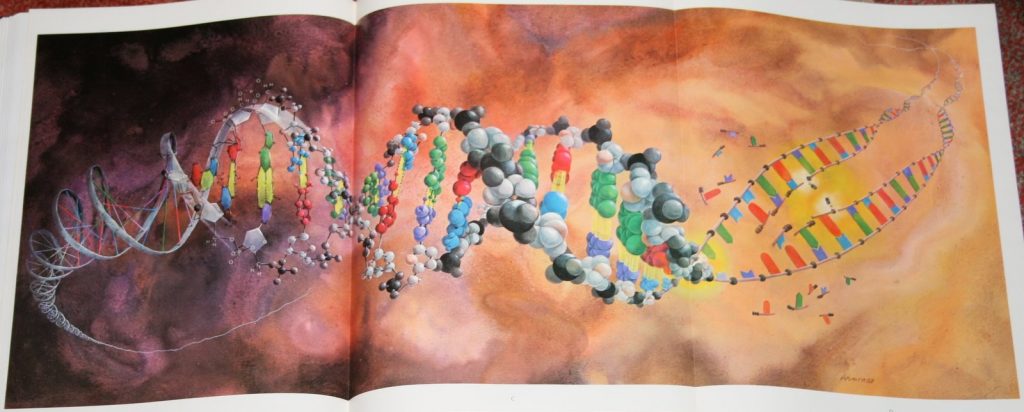

It’s a core principle of post-industrial political economy that knowledge is not just a product created by economic and cultural activity, but a key part of the means of production (i.e., cultural capital). Software, patentable ideas, and copyrighted content of all sorts are the basis for a wide variety of production. Software is used to create more software as well as visual art, fiction, music, scientific knowledge, journalism, etc. (See “Copyleft vs. Copyright: A Marxist Critique“, Johan Söderberg, First Monday.) And all those things are inputs into the production of new cultural products. The idea of “remix culture” that Larry Lessig has been promoting recently emphasizes that in the digital realm, there’s no clear distinction between cultural products and means of cultural production; art builds on art. (Lessig, however, has resisted associations between the Creative Commons cultural agenda and the Marxist tradition, an attitude that has brought attacks from the left, e.g., the Libre Society.)

Modern intellectual property regimes are designed to turn non-material means of production into things that can be owned. And the free software and free culture movements are about collective ownership of those means of production.

Also implicit in the free culture movement’s celebration of participatory culture and user-generated content (see my post on “LOLcats as Soulcraft“) is the set of arguments advanced by later theorists about the commodification of culture. A society that consumes the products of a culture industry is very different from one in which produces and consumers of cultural content are the same people–even if the cultural content created was the same (which of course would not be the case).

What can a Marxist viewpoint tell us about where Wikimedia and free culture can or should go from here? One possibility is online “social networking”. The Wikimedia community, and until recently even the free software movement, hasn’t paid much attention to social networking or offered serious competition to the proprietary sites like Facebook, MySpace, Twitter, etc. But if current agenda is about providing access to digital cultural capital (i.e., knowledge and other intellectual works), the next logical step is to provide freer, more egalitarian access to social capital as well. Facebook, MySpace and other services do this to some extent, but they are structured as vehicles for advertising and the furtherance of consumer culture, and in fact are more focused on commoditizing the social capital users bring into the system than helping users generate new social capital. (Thus, many people have noted that “social networking sites” is a misnomer for most of those services, since they are really about reinforcing existing social networks, not creating new connections.)

The Wikimedia community, in particular, has taken a dim view of anything that smacks of mere social networking (or worse, MMORPGs), as if cultural capital is important but social capital is not. But from a Marxist perspective, it’s easier to see how intertwined the two are and how both are necessary to maintain a healthy free culture ecosystem.

Wikimedia and the rest of the free culture community, then, ought to get serious about supporting OpenMicroBlogging (the identi.ca protocol) and other existing alternatives to proprietary social networking and culture sites, and even perhaps starting a competitor to MySpace and Facebook. (See some of the proposals I’m supporting on Wikimedia Strategic Planning wiki in this vein.)